Standard recap: I’m slowly going through AABC’s one-million-plus back-issue room, restocking the boxes on the sales floor and pulling stuff to sell as discount/overstock/special items (these are featured at the discount racks at the west end of the store for a couple of weeks after each post, and then go to the discount racks on the east end of the store for a few weeks, and then disappear into our warehouses, so get them while you can). I’m going through the alphabet backwards (don’t ask), and at my speed (especially with the school semester starting up again), this amounts to a two-and-a-half-year project. This week, we’re featuring Marvel’s Master of the Mystic Arts:

Standard recap: I’m slowly going through AABC’s one-million-plus back-issue room, restocking the boxes on the sales floor and pulling stuff to sell as discount/overstock/special items (these are featured at the discount racks at the west end of the store for a couple of weeks after each post, and then go to the discount racks on the east end of the store for a few weeks, and then disappear into our warehouses, so get them while you can). I’m going through the alphabet backwards (don’t ask), and at my speed (especially with the school semester starting up again), this amounts to a two-and-a-half-year project. This week, we’re featuring Marvel’s Master of the Mystic Arts:

Dr. Strange

Dr. Stephen Strange is the “other” Marvel mainstay created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko (after Spider-Man, of course), and first appears as the back-up story in Strange Tales #110, in 1963. He has a typical Stan Lee fairy-tale, there’s-a-lesson-here origin: he’s a world-renowned surgeon, arrogant and uncaring, but then gets in a drunken car wreck that damages his hands, and makes it impossible for him to do surgery any more. Bitter and depressed, he schleps around the globe, eventually ending up at one of those hidden-temple Shangri-La Far East outposts, where he encounters the Ancient One, a  magician/guru, and his disciple, Baron Mordo. Strange accidentally discovers that Mordo is really a villain, who’s learning the Ancient One’s arts for evil, and, revealing his buried heroism, risks his life to warn everyone about it and stop Mordo’s plans; Mordo ends up banished, and Strange becomes the Ancient One’s new disciple. All of this is rendered with imagination and grace by Ditko, whose ability to draw weird other dimensions, and make mystical powers like “bolts of bedevilment” seem both realistic and trippy/cool, turns the origin, and the tales that follow it, into ’60s hippy classics. Ditko leaves the book in 1966, with issue #146, but Strange soldiers on — drawn by, among others, Bill Everett, Marie Severin, Dan Adkins and Jim Steranko — and eventually takes over the comic, as Strange Tales becomes Dr.

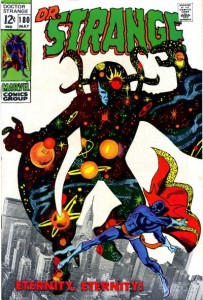

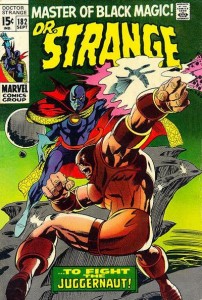

magician/guru, and his disciple, Baron Mordo. Strange accidentally discovers that Mordo is really a villain, who’s learning the Ancient One’s arts for evil, and, revealing his buried heroism, risks his life to warn everyone about it and stop Mordo’s plans; Mordo ends up banished, and Strange becomes the Ancient One’s new disciple. All of this is rendered with imagination and grace by Ditko, whose ability to draw weird other dimensions, and make mystical powers like “bolts of bedevilment” seem both realistic and trippy/cool, turns the origin, and the tales that follow it, into ’60s hippy classics. Ditko leaves the book in 1966, with issue #146, but Strange soldiers on — drawn by, among others, Bill Everett, Marie Severin, Dan Adkins and Jim Steranko — and eventually takes over the comic, as Strange Tales becomes Dr. Strange with issue #169, in 1968. In issue #172, he receives his second great artist, Gene Colan, who draws him through the end of the book’s run, with issue #183, in 1969.

Strange with issue #169, in 1968. In issue #172, he receives his second great artist, Gene Colan, who draws him through the end of the book’s run, with issue #183, in 1969.

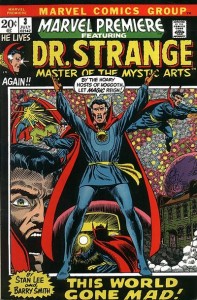

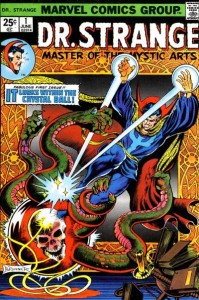

Strange is relegated to guest-star status for a while after that, but returns to his own stories in 1972, in the try-out title Marvel Premiere. His first appearance there, in issue #3, is written by Lee and drawn by Barry Windsor-Smith, and is a small masterpiece of mood and cool art (Strange, with his mystical and fantasy elements, has always attracted good artists). Lee only writes the first issue, and  Smith only stays around for the next one, #4; there’s some flailing around after that, but in issue #9 the team of Steve Englehart and Frank Brunner takes over, and quickly makes the book a cult favorite, by doing things like killing the Ancient One, and having Dr. Strange travel to the beginning of the universe and meet God; after Marvel Premier #14, in fact, the book proves popular enough to get its own title again, and Dr. Strange #1 appears in June, 1974, still by Englehart and Brunner. That artist leaves after issue #5, but his replacement is Gene Colan, and he and Englehart, during the next year, deliver one of the best sustained Marvel runs of the ’70s: Dr. Strange #s 6-

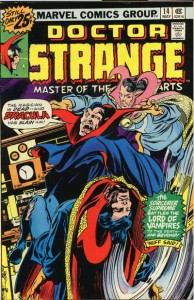

Smith only stays around for the next one, #4; there’s some flailing around after that, but in issue #9 the team of Steve Englehart and Frank Brunner takes over, and quickly makes the book a cult favorite, by doing things like killing the Ancient One, and having Dr. Strange travel to the beginning of the universe and meet God; after Marvel Premier #14, in fact, the book proves popular enough to get its own title again, and Dr. Strange #1 appears in June, 1974, still by Englehart and Brunner. That artist leaves after issue #5, but his replacement is Gene Colan, and he and Englehart, during the next year, deliver one of the best sustained Marvel runs of the ’70s: Dr. Strange #s 6- 18, among other things, destroy the world and remake it, have Dr. Strange fight Dracula (in a two-parter that crosses over with Colan’s second title, Tomb of Dracula), and send Dr. Strange to Hell. Only a few of these issues are on the discount racks, but they’re surprisingly cheap, and available in the regular back-issue boxes for $5 or less each; if you’ve never read them, you’re missing some wonderful, influential work.

18, among other things, destroy the world and remake it, have Dr. Strange fight Dracula (in a two-parter that crosses over with Colan’s second title, Tomb of Dracula), and send Dr. Strange to Hell. Only a few of these issues are on the discount racks, but they’re surprisingly cheap, and available in the regular back-issue boxes for $5 or less each; if you’ve never read them, you’re missing some wonderful, influential work.

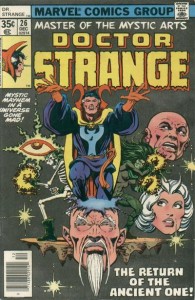

Unfortunately, just when the book is at its peak Englehart gets into a dispute with Marvel’s new editor-in-chief, Gerry Conway, and leaves the company; that leaves the book to try to pick up the pieces, and it goes into musical-creator  mode for awhile. Part of the problem is that not all writers are compatible with the Doctor — Marv Wolfman and Chris Clarement, among others, try and mostly fail — but there are some interesting moments: Jim Starlin writing issues #24-26; Roger Stern and Tom Sutton on #s 27-30; Claremont and Colan on #s 38-45 (Claremont doesn’t add much, but the Colan art is worth a look). The next really decent run, though, starts with issue #47, as Roger Stern (who does prove to be a great Doc writer) teams with Colan for that issue, and then with Marshall Rogers from #48-53, Michael Golden in #55, and Paul Smith in #56. Stern stays

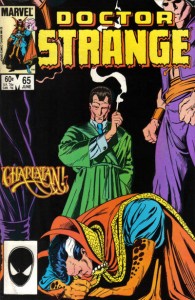

mode for awhile. Part of the problem is that not all writers are compatible with the Doctor — Marv Wolfman and Chris Clarement, among others, try and mostly fail — but there are some interesting moments: Jim Starlin writing issues #24-26; Roger Stern and Tom Sutton on #s 27-30; Claremont and Colan on #s 38-45 (Claremont doesn’t add much, but the Colan art is worth a look). The next really decent run, though, starts with issue #47, as Roger Stern (who does prove to be a great Doc writer) teams with Colan for that issue, and then with Marshall Rogers from #48-53, Michael Golden in #55, and Paul Smith in #56. Stern stays on with some lesser artists (although there’s another battle with Dracula in #s 60-62 that banishes all vampires from the Marvel Universe for awhile that’s pretty good), but then Smith returns in issue #65, and he and Stern have a nice little set of stories through issue #73. Both leave at that point, though, and the book only lasts a few more months, ending with issue #81 in February, 1987.

on with some lesser artists (although there’s another battle with Dracula in #s 60-62 that banishes all vampires from the Marvel Universe for awhile that’s pretty good), but then Smith returns in issue #65, and he and Stern have a nice little set of stories through issue #73. Both leave at that point, though, and the book only lasts a few more months, ending with issue #81 in February, 1987.

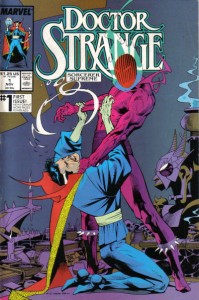

Strange’s third volume begins about a year and a half later, in November, 1988, and is titled Doctor Strange, Sorcerer Supreme; the initial writer is Peter Gillis (who’d been the scripter for the last few issues of the previous series), with art chores by Richard Case (who’d eventually go on to DC Vertigo titles like Doom Patrol); that team only stays for the first four issues, though, and then is replaced by Roy Thomas (with, as co-writer, his wife Dann) and Jackson Guice, an association that proves fruitful enough to last for two years, through

Strange’s third volume begins about a year and a half later, in November, 1988, and is titled Doctor Strange, Sorcerer Supreme; the initial writer is Peter Gillis (who’d been the scripter for the last few issues of the previous series), with art chores by Richard Case (who’d eventually go on to DC Vertigo titles like Doom Patrol); that team only stays for the first four issues, though, and then is replaced by Roy Thomas (with, as co-writer, his wife Dann) and Jackson Guice, an association that proves fruitful enough to last for two years, through issue #24 (although there are a few fill-in artists: Richard Valentino in #17, and Gene Colan in #19). The most notorious issue of this run comes, not from any plot or character development, but from a cover: on issue #15, Guice swiped an image from one of Christian singer Amy Grant’s albums, and Grant, upset at both the theft and the fact that it was used on a “demonic” character’s cover, sued Marvel, who eventually settled out of court. The Thomases stay on after that, but with a series of undistinguished artists (Geof Isherwood being the most long-lived); even the plots become less memorable, because this is a period

issue #24 (although there are a few fill-in artists: Richard Valentino in #17, and Gene Colan in #19). The most notorious issue of this run comes, not from any plot or character development, but from a cover: on issue #15, Guice swiped an image from one of Christian singer Amy Grant’s albums, and Grant, upset at both the theft and the fact that it was used on a “demonic” character’s cover, sued Marvel, who eventually settled out of court. The Thomases stay on after that, but with a series of undistinguished artists (Geof Isherwood being the most long-lived); even the plots become less memorable, because this is a period  — the early ’90s — when Marvel is heavily into cosmic crossovers — Infinity Gauntlet, etc. — and Dr. Strange keeps tying into them, sacrificing any individual story for the larger mega-event. Thomas leaves with issue #47, and when scripter Len Kaminski replaces him the descent into mediocrity is complete. There are a couple of glimmers — in issue #60, a big crossover with the other Marvel occult titles like Morbius and Spirits of Vengeance (they’re all part of the group of books that Marvel marketed as the “Midnight Sons”) takes place, and Dr. Strange gets broken into three different beings;

— the early ’90s — when Marvel is heavily into cosmic crossovers — Infinity Gauntlet, etc. — and Dr. Strange keeps tying into them, sacrificing any individual story for the larger mega-event. Thomas leaves with issue #47, and when scripter Len Kaminski replaces him the descent into mediocrity is complete. There are a couple of glimmers — in issue #60, a big crossover with the other Marvel occult titles like Morbius and Spirits of Vengeance (they’re all part of the group of books that Marvel marketed as the “Midnight Sons”) takes place, and Dr. Strange gets broken into three different beings; this story, by David Quinn and Melvin Rubi (at first), starts promisingly but then lasts through what seems forever, and sends Strange through so many makeovers and changes that the reader gets exhausted trying to keep it all straight. Points of note are issues #70-73, with art by Peter Gross; #75, by Mark Buckingham; #76, introducing a long-haired version of Strange by Gross that looks eerily like the older Tim from his Books of Magic series at DC Vertigo; #s 78 and 79, by Marie Severin; #80, featuring another new look for the character, this one written by Warren Ellis and drawn by Buckingham; #82, half by Buckingham and half by Gary Frank; and #s 84-90, drawn by Buckingham and with a story by J.M. DeMatteis — and that ends the series, in January 1996, and is the last time that Dr. Strange has had his own ongoing title.

this story, by David Quinn and Melvin Rubi (at first), starts promisingly but then lasts through what seems forever, and sends Strange through so many makeovers and changes that the reader gets exhausted trying to keep it all straight. Points of note are issues #70-73, with art by Peter Gross; #75, by Mark Buckingham; #76, introducing a long-haired version of Strange by Gross that looks eerily like the older Tim from his Books of Magic series at DC Vertigo; #s 78 and 79, by Marie Severin; #80, featuring another new look for the character, this one written by Warren Ellis and drawn by Buckingham; #82, half by Buckingham and half by Gary Frank; and #s 84-90, drawn by Buckingham and with a story by J.M. DeMatteis — and that ends the series, in January 1996, and is the last time that Dr. Strange has had his own ongoing title.

That’s not to say that the character hasn’t been around, of course. There’ve been the occasional mini-series (J. Michael Straczynski and Brandon Peterson did the six-issue origin reboot Strange in 2004, while Mark Waid and Emma Rios contributed the four-issue Strange in 2010), and the Doctor has been a member of the Avengers (well, the New Avengers) during most of Brian Michael Bendis’s tenure on that book, as well as appearing in the current revival of The Defenders. Will audiences ever warm to him again? Sure: if comics history has proven anything, it’s that, with the right writer and the right artist, any character can rise from the comics graveyard. Given his past, the Master of the Mystic Arts is a better candidate than most.

That’s not to say that the character hasn’t been around, of course. There’ve been the occasional mini-series (J. Michael Straczynski and Brandon Peterson did the six-issue origin reboot Strange in 2004, while Mark Waid and Emma Rios contributed the four-issue Strange in 2010), and the Doctor has been a member of the Avengers (well, the New Avengers) during most of Brian Michael Bendis’s tenure on that book, as well as appearing in the current revival of The Defenders. Will audiences ever warm to him again? Sure: if comics history has proven anything, it’s that, with the right writer and the right artist, any character can rise from the comics graveyard. Given his past, the Master of the Mystic Arts is a better candidate than most.